Get Started

Overview

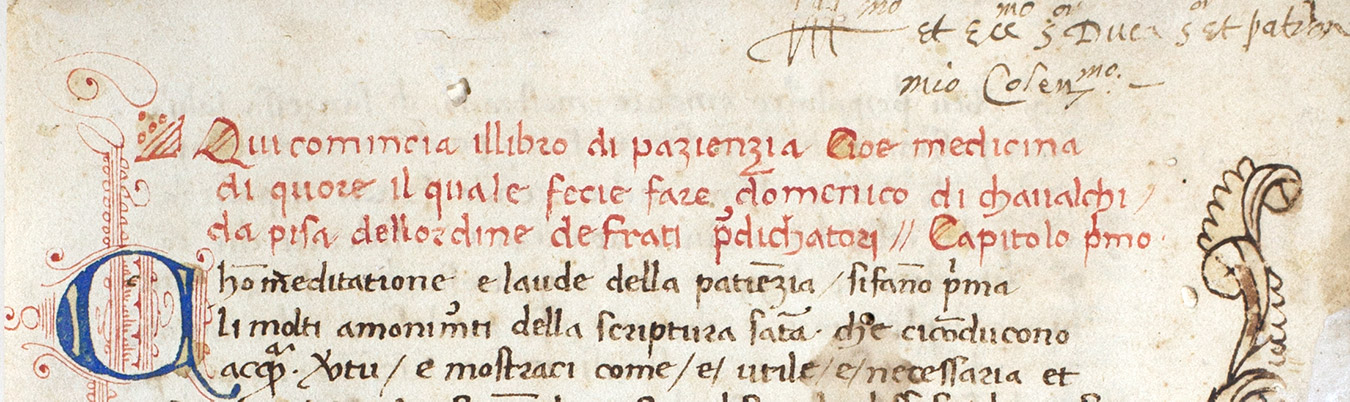

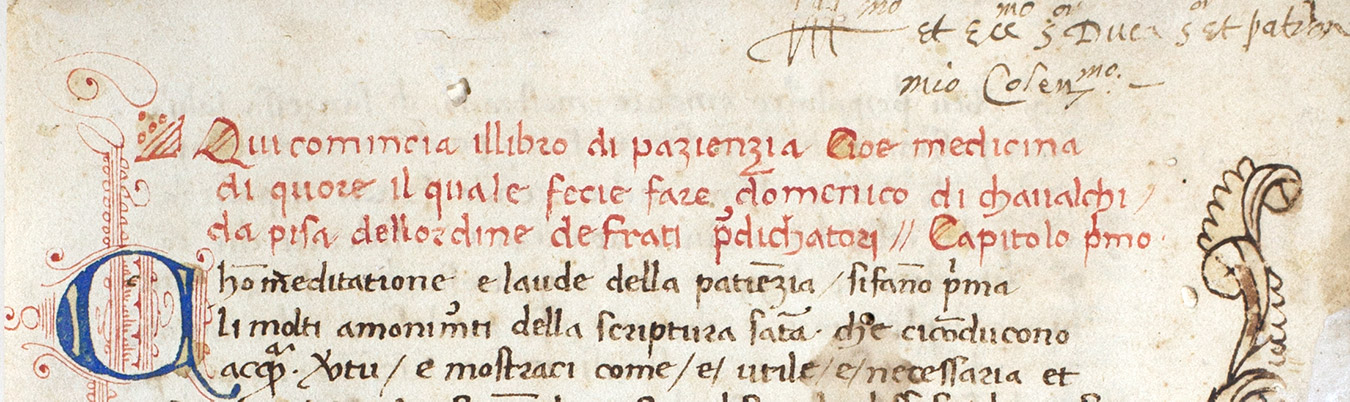

The Italian Paleography website presents 102 Italian documents and manuscripts written between 1300 and 1700, with tools for deciphering them and learning about their social, cultural, and institutional settings. The site includes:

- digitized images of 102 manuscripts and documents;

- TPEN, a digital tool to actively transcribe manuscripts and documents;

- transcriptions and background essays for each item;

- a selection of calligraphy books and historical manuscript maps;

- a handbook of Italian vernacular scripts;

- additional resources, including a glossary, list of abbreviations and symbols, dictionaries, and teaching materials.

What is Italian Paleography?

Paleography is the study of the history of handwriting and scripts in books, manuscripts, and all sorts of documents, including drawings, printed material, epigraphs, inscriptions, and writings appearing on any object (coins, vases, frames, or even walls). Paleography also examines the physical construction of different textual sources and their functions, analyzing the relationship between these containers, their scripts, and their contents.

According to Jean Mallon (Mallon

1952), a famed 20th-century French paleographer, paleography is the study of written cultures, that is the production, formal graphic characteristics, and social uses of scripts and textual witnesses. The goal of the discipline is therefore to investigate and to understand the socio-cultural instances that led to the production and transmission of written traces: each particular writing is the product of a specific culture and a specific time-space.

Why study Paleography

The act of writing establishes hierarchies and social disparities: there was and still is no society in which everyone is able to write. The issue of literacy is strictly linked to the distribution of power and wealth. Literacy and access to reading and writing has been a powerful source of political control throughout human history. Confining a percentage of the population outside the basic literacy parameters prevents them from having access to documents and memory. Written texts of any sort, in fact, enable communication through time and space, leaving concrete memory of a given society. Writings from a certain time and place also influence the way posterity reads, transmits, and interprets the history of the society that produced the specific writing. When we study history, we often study “sources” or a particular written story that was transcribed at a particular time and transmitted through different material witnesses. A paleographer is also, therefore, a historian of written cultures: through paleographical and codicological investigations, s/he can study the index of literacy, its geographic, social, and political values in ancient civilizations up until today. (Ref. Petrucci 2002, vi-vii)

How to analyze a script

When we approach a handwritten text, through an examination of its materiality, graphic appearance, and cultural context, six main questions, both technical (1-4) and interpretative (5-6), can be answered (Petrucci 2002):

- What is this written text?

- When was it written?

- Where was it written?

- How, with what techniques and instruments and on what materials was it written?

- Who wrote the text? What was the socio-cultural background of the author or scribe?

- Why was the text written? In the particular time and space it was produced, what could have been its social and ideological goals?

These questions help us to identify, describe, and understand the social and cultural context in which a specific text and its script were produced. For a list of the main terms associated with paleography and manuscript studies in general, see [Glossary](https://centerfordigitalhumanities.github.io/Newberry-Italian-paleography/glossary).

Tips and Tricks

Before transcribing:

- Before starting your transcription, clearly set your standards: how to transcribe abbreviations; modernize or maintain original spaces, divisions, and punctuation; maintain or ignore line breaks; treatment of marginalia, etc.

- Keep in mind: you do not need to be able to read every single word and every single character on your first try. If you find yourself in doubt about a word or even a single character, continue your transcription to the end of the page. There might be another word and/or character further on that can help you understand the parts you skipped on a first try.

- Word of advice: go over a page of transcription more than once. You can always find new details that can help you to complete or to correct your first transcription.

While transcribing:

- Proceed line by line, word by word.

- Annotate common patterns: common ligatures, shapes of specific letters, common abbreviations, specific scribal patterns, etc.

- Pay attention to: abbreviations and diacritic marks, punctuation, initials, paragraph markers, erasures, etc.

- Stay consistent with your transcribing practices.

- Use the context to help you with your transcription. Remember that, most of the time, you are not transcribing an arbitrary juxtaposition of characters: the content (and context) of what you are transcribing can help you make sense of difficult-to-read words.

After transcribing:

- Closely re-read and edit your transcription: you might recognize letters and/or words you were not able to the first time.

Brief History of Paleography

- 17th century: The first concrete but still partial paleography studies were conducted. A crucial moment was the publication of Jean Mabillon’s De Re Diplomatica in 1681, an essay on Medieval Latin paleography and diplomacy. For the first time, Mabillon attempted a classification and description of different kinds of scripts.

- 18th century: The first paleographic publications were disseminated. Paleography was at this stage still dependent on other disciplines, especially diplomatic. Important publication: Bernard de Montfaucon’s Paleographia graeca in 1708. Moreover, in Italy in 1727, Scipione Maffei published his Istoria diplomatica. While in France, mid century, Benedictine monk Charles Toustain published his Nouveau traité de diplomatique.

- 19th century: In the 1800s, paleography established itself as an independent scientific discipline. The growing production of facsimile photographs allowed for paleographic investigations and comparisons between different texts (often in different physical places).

- 20th century: Paleography now investigated not only how to classify different scripts, but also how to date and localize them. Ludwig Traube in Germany and Léopold-Victorin Delisle in France were among the pioneers of this time, including paleography in the history of cultures and civilizations and developing it as an essential discipline, part of broader philological studies. In Italy, during the second half of the 20th century, Giorgio Cencetti published a first comprehensive history of Latin scripts. His works and methods would influence Emanuele Casamassima, Armando Petrucci, Guglielmo Cavallo, and Alessandro Pratesi.

For a detailed overview of Italian scripts, refer to the Handbook for Italian paleography available here.